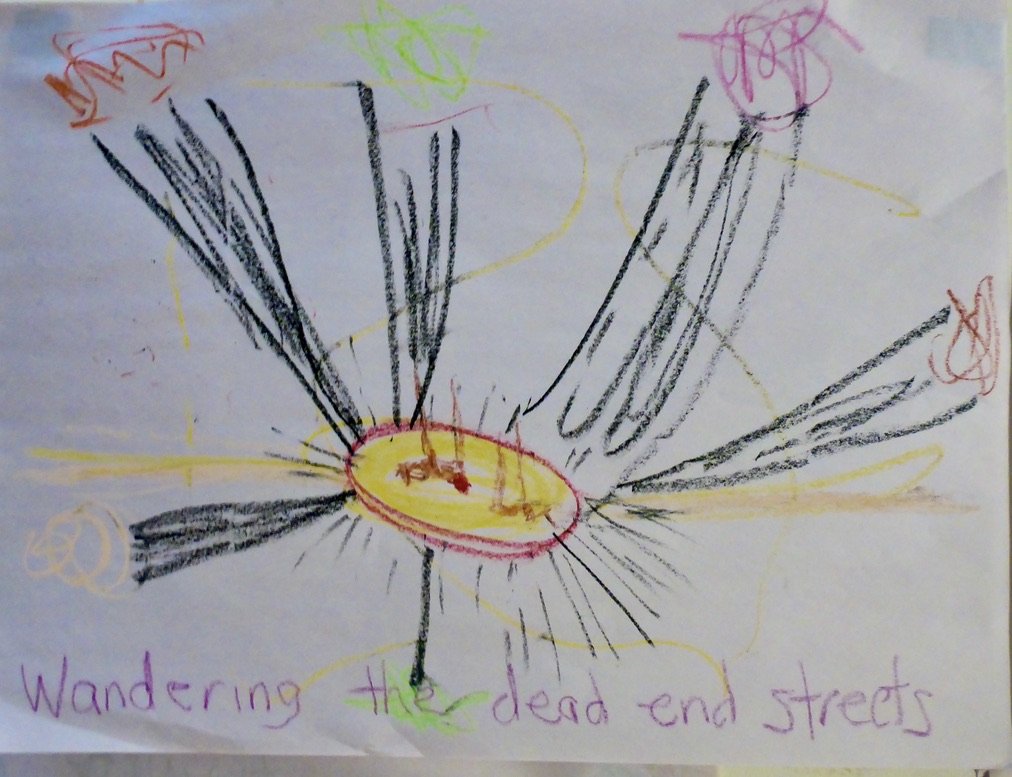

Down the Backroads and Dead-end Streets of the Creative Process

Down the Backroads and Dead-end Streets of the Creative Process

Making a New Dance: The Crabbit Wee Tailors of FarforJessica and I are making a new dance. It’s the first thing we’ve choreographed together since Primo Tempore more than 4 years ago. Since then I’ve been deeply into my songwriting and performing and Jessica has created some wonderful pieces with her niece Laura. Given this time away from making dances, coming back to it is fascinating and illuminating. It offers me lots of new perspective on the creative process in both dance and music.

Choreographing dances is hard for me. I’ve always found it so. Making up movements, being free and creative improvisationally or socially is easy. But the second I try to repeat and set the movement the editor/critic shows up and something feels lost. You can work for hours and hours to come up with 30 seconds of material and then dump it in the next rehearsal. And the clock keeps ticking -- there is always a deadline – the curtain will rise ready or not. In music, if the song is not done, just play a different song.

When Jessica and I make dances, we start with almost nothing. We don’t usually choreograph to music. We add the music or sound later if at all. We don’t tend to start with a story or narrative. Sometimes we start with a prop or some materials. Maybe a line or two of dialogue. Sometimes there is a character. We then try to let the materials, or prop, or character speak to us, tell us how it moves, what its relationship is to the space, each other, and other people.

We are looking for moments of sensation (either live or looking at video) that FIT -- that feel real and alive -- that feel like something rather than nothing. Little by little it takes shape through those sensations, and we layer in sound, choreography, and other elements.

Why do we have to make it so hard on ourselves? Why can’t we just start with a piece of music and choreograph a dance to it? It seems to work well for other people. We just don’t usually work that way.

The most striking thing for me is to realize how many ideas end up in the trash. A flash of insight, a first-thing-in-the-morning or middle of the night idea, the shiny object, a perfect image appears -- the ANSWER. Then as we work it out it turns out to be a cartoon that can’t be accomplished by human bodies on this particular planet. Or it’s just dumb, silly, or somehow doesn’t fit. Or it’s a really nice movement but doesn’t read or look like much from the outside. So, you turn around and back out of that tunnel, giving up the shiny object that was going to be the answer to all your confusion and start again. Each dead end is learning but each one takes a toll of confidence and spirit. This takes a ridiculous amount of time and the internal strength required to weather so many failures is truly astonishing.

In his study of creative individuals Csikszentmihalyi reported that even the very best artists, scientists and thinkers produce more mediocre work than amazing work and that for every great world changing idea there might be hundreds that were trashed. The key difference in people who consistently make great or important work is not the number of ideas they have but their ability to discern which ideas are most promising and which don’t deserve the time to pursue. In other words, their acute sense of what fits and is doable is the main distinguishing characteristic of their creative prowess. Going a little way down a path and then recognizing it’s not going to work out is a crucial part of the process as long as you a) don’t spend too much time on each wrong path, b) don’t give up on a path just because it is hard, c) don’t get so discouraged that you stop trying, or d) randomly choose a path to just escape the struggle. I will admit to having ended up on d) on many occasions as a way to get through the block and on to the next part which might inform the choice. And d) might turn out to be the right (or right enough) choice because of what comes next. But knowing a lot about the creative process and recognizing that it can be grueling with lots of failure doesn’t make it any easier!

Our self-editors are fierce and unforgiving. In co-choreography we’ve got two of these mighty overseers at work. These picky, unforgiving characters live inside two people who desperately want to be positive, supportive, and helpful, and who are looking for the slightest clue that we’re onto something or at least have a path forward. But the other person is not a student of ours who we would be gentle with, trying to “stabilize the discomfort” as our friend Phyllis Lamhut puts it. No, we are two people with a long personal, creative, professional history. Our joy in dancing together, feeling our connected energy and timing, appreciating the other’s body and mind, can be derailed by the blunt sword of self-criticism and whatever lingering annoyances might have popped up in the last 24 hours (or 38 years for that matter).

When Jessica and I decided to start our own dance company in the late 90’s we chose to have other people choreograph works for us. We know lots of amazing choreographers and the varied repertoire we built was satisfying and the process was fun (mostly) and always exciting. Our previous attempts at choreographing together had ended in frustration and conflict. I’m not sure if there was a moment that we were able to overcome the obstacles, but we started small with a 4 minutes piece called Native Tongue and it expanded from there to a number of extended pieces, finally moving into full evening dance/theater works.

What do we do that help us get through all these blocks and self-doubt? Here’s some of our solutions.

1. Integrate. I learned the process of Integration in college in New Mexico with Gerrie Glover. This form of the process was developed and taught by Juanita Sagan and AA Leath at the Institute for Creative and Artistic Development and it has been a cornerstone of both my artistic and teaching lives ever since. In short, Integration is a way to get present in the moment, leave a lot of emotional baggage outside the studio, and focus on the work. It takes time at the start of every rehearsal, but it is well worth it in terms of the productivity of the rest of the time. A description of the process can be found at: https://barryoreck.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Integration.pdf

2. Make a bad dance. When we set out to intentionally make something terrible, we can sometimes trick the editors into taking a nap and make something really good. Sometimes bad is bad but often the drive for the truly terrible works a whole lot better than trying to make the best piece that’s ever been created.

3. Make deadlines (and know that anything can happen up to the moment you go onstage). Early showings to others remind us that we are in the exact position of our students who we encourage to be brave and objective and open to outside responses. We don’t have to change anything or accept the opinions of the audience, but we need to create some sort of shape to the work and get some outside perspective to help us move forward. Having opened ourselves to responses we have to be willing to “cut it back and make it bleed again” as Hanya Holm once said. We’ve changed entire sections, openings, endings, transitions between dress rehearsal and the performance. Exciting, scary, alive.

I’ll reflect more on my process in songwriting in my next post but for now I will only say it’s way easier for me to make up tunes. And the payoff in music is both more immediate when you pick up a guitar and play for someone or jam with friends, and more lasting when you record a song or make an album. The payoff and satisfaction in the creation of dance is the process itself. It’s got to be. At the end you get to perform this piece you’ve spent months or years on for a weekend perhaps. You’ll hear nice things from your friends and try to remember what they said the next morning. You’ll have a record of it on video. That’s all. No CD’s to share, no downloads, no corner bar or club to play at, and certainly no money. Just a piece of art in time and space. A piece of your imagination shaped by focus and time to become something that involves your whole being.

I’m so happy to be back in the struggle.